-

-

-

-

-

Deana, 12, enjoys an ice-cream with her mum Julie, on the seafront in Port Talbot, Wales. From the series The Big O, an intimate porttrait of the children behind the obesity statstics in the UK. It is estimated that 1 in 3 children in the UK are now classified as obese or overweight.

-

The Big O

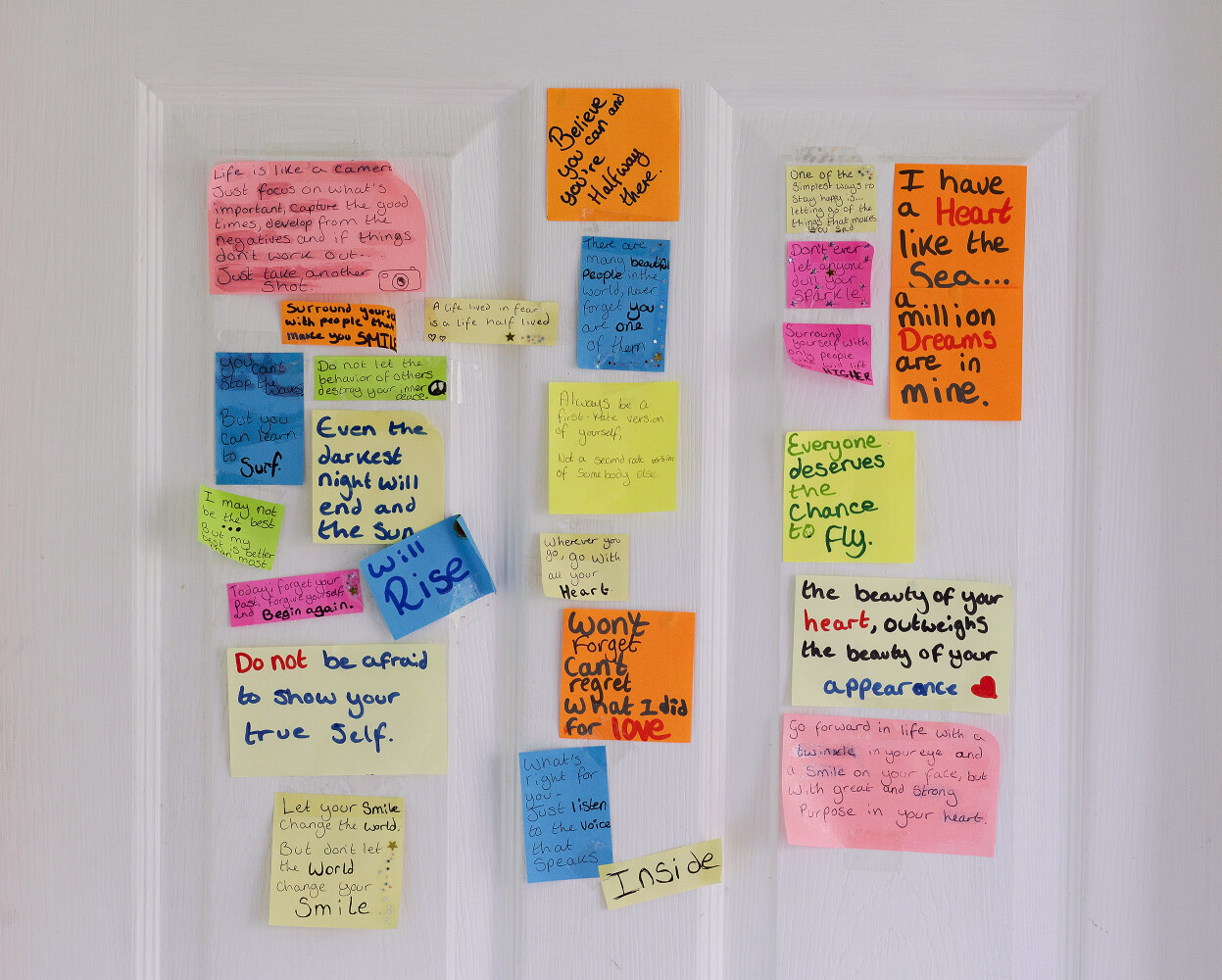

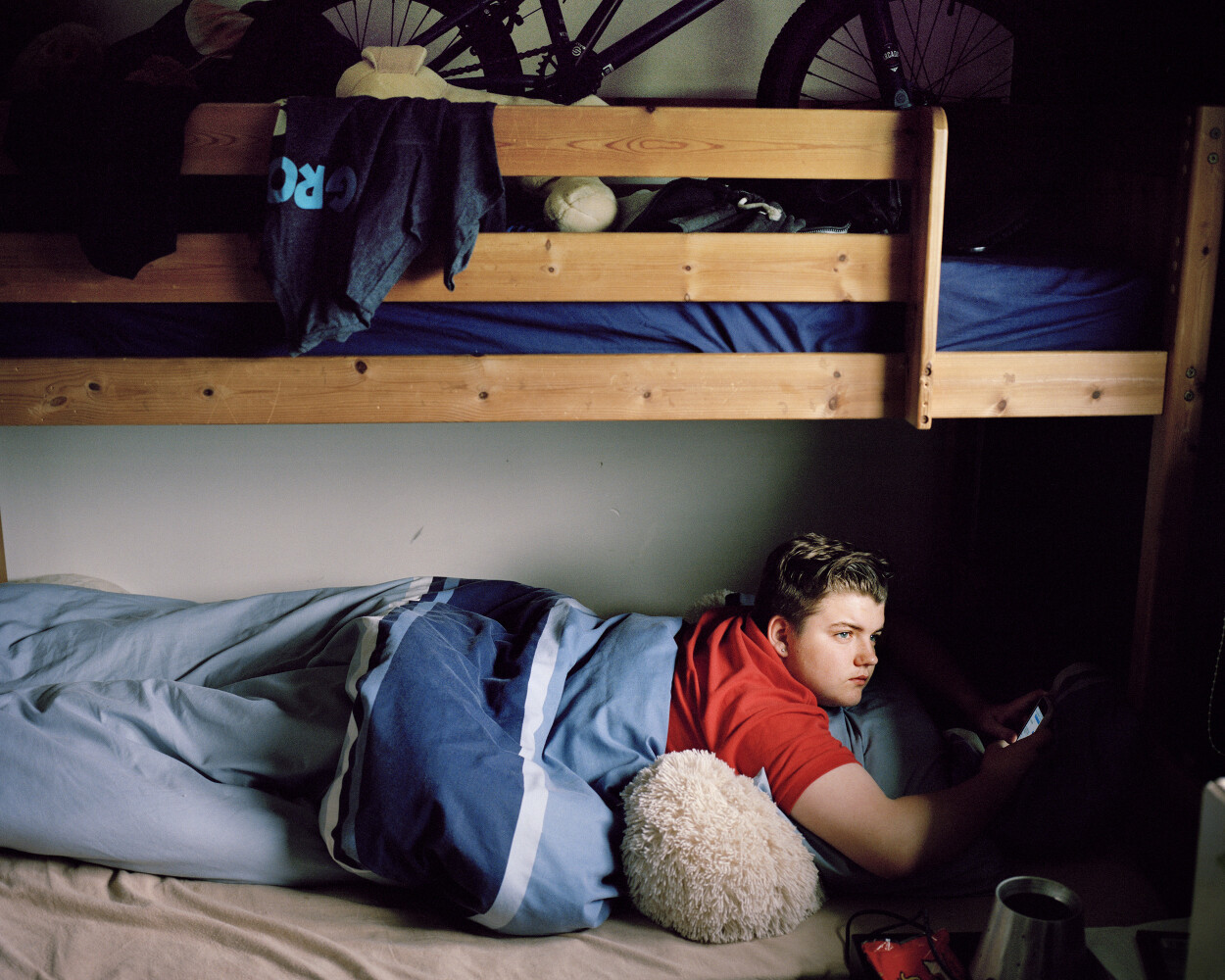

Our teenage years are arguably the most awkward of our lives. Whether it’s acne, depression, body dysmorphia, anger management, or any other number of issues, the turbulence of hormones and physical, mental and emotional changes, all while navigating school.

But imagine having all that going on, and being fat.

Growing up fat myself, I believed that if I wasn’t fat, then somehow everything else in my life would be problem-free. Obesity isn’t a hidden problem. It’s one that you wear, one that everyone can see. One that makes it harder to run away from, and ultimately harder to address.

The psychological effects of being fat in a society that values thinness, interest me as much as the obvious health impairments. Being overweight or obese is deemed to be self-inflicted, even a lifestyle choice, and the ‘culprit’ labelled, greedy, lazy, lacking in discipline. Obesity has taken over from cancer as the thing to fear, with the ‘Big O’ and its stigma and discrimination following the overweight from the schoolyard into the workplace and beyond.

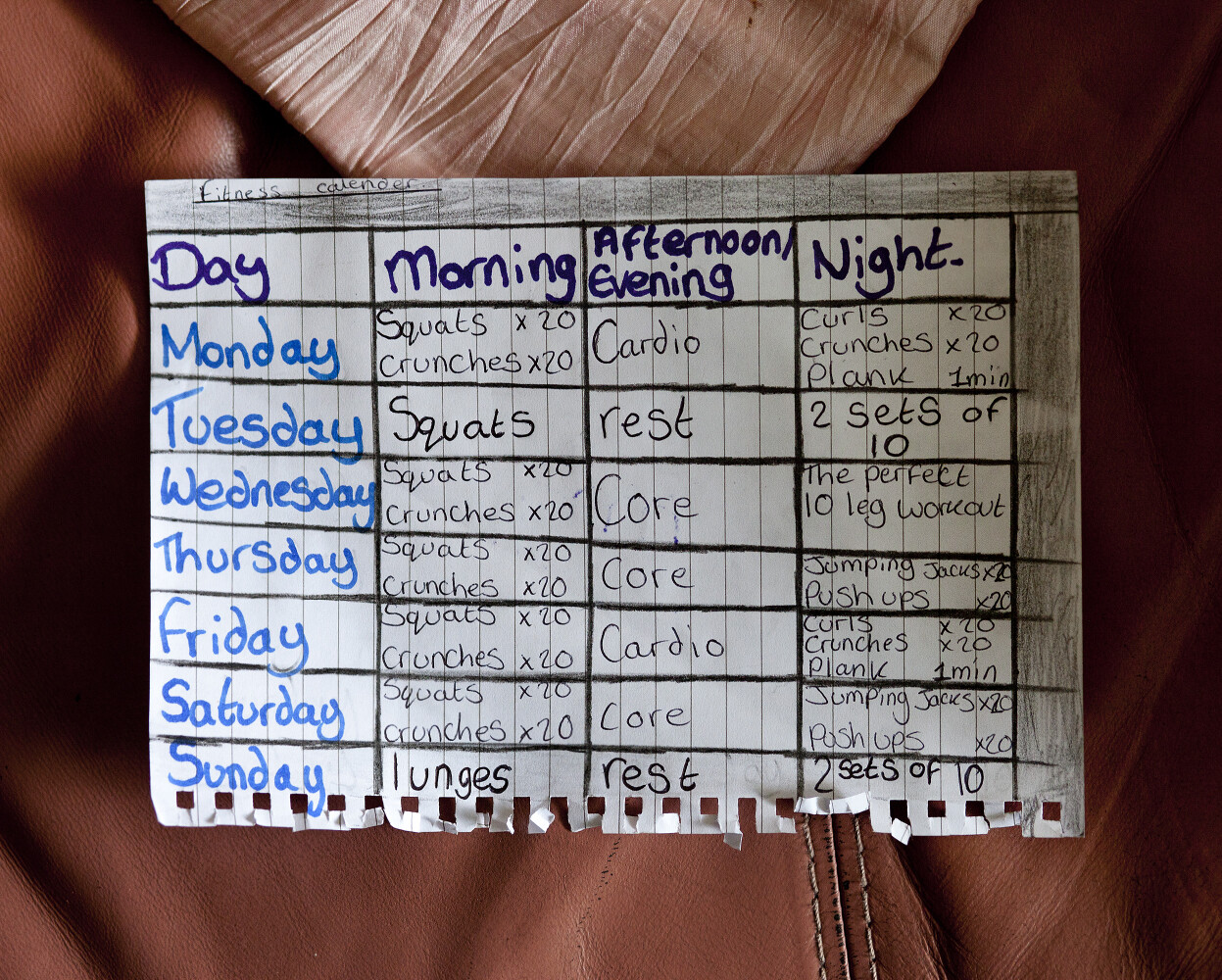

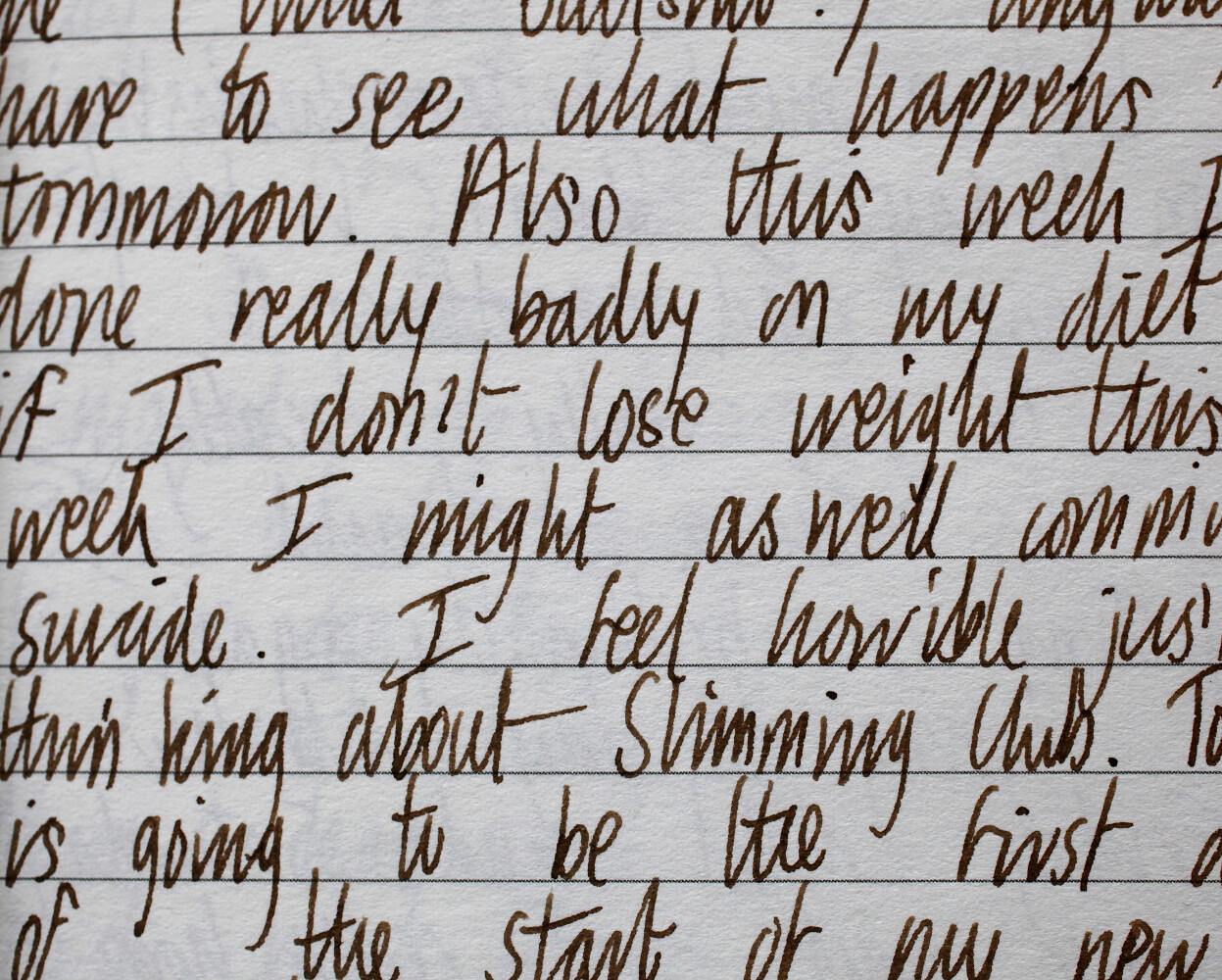

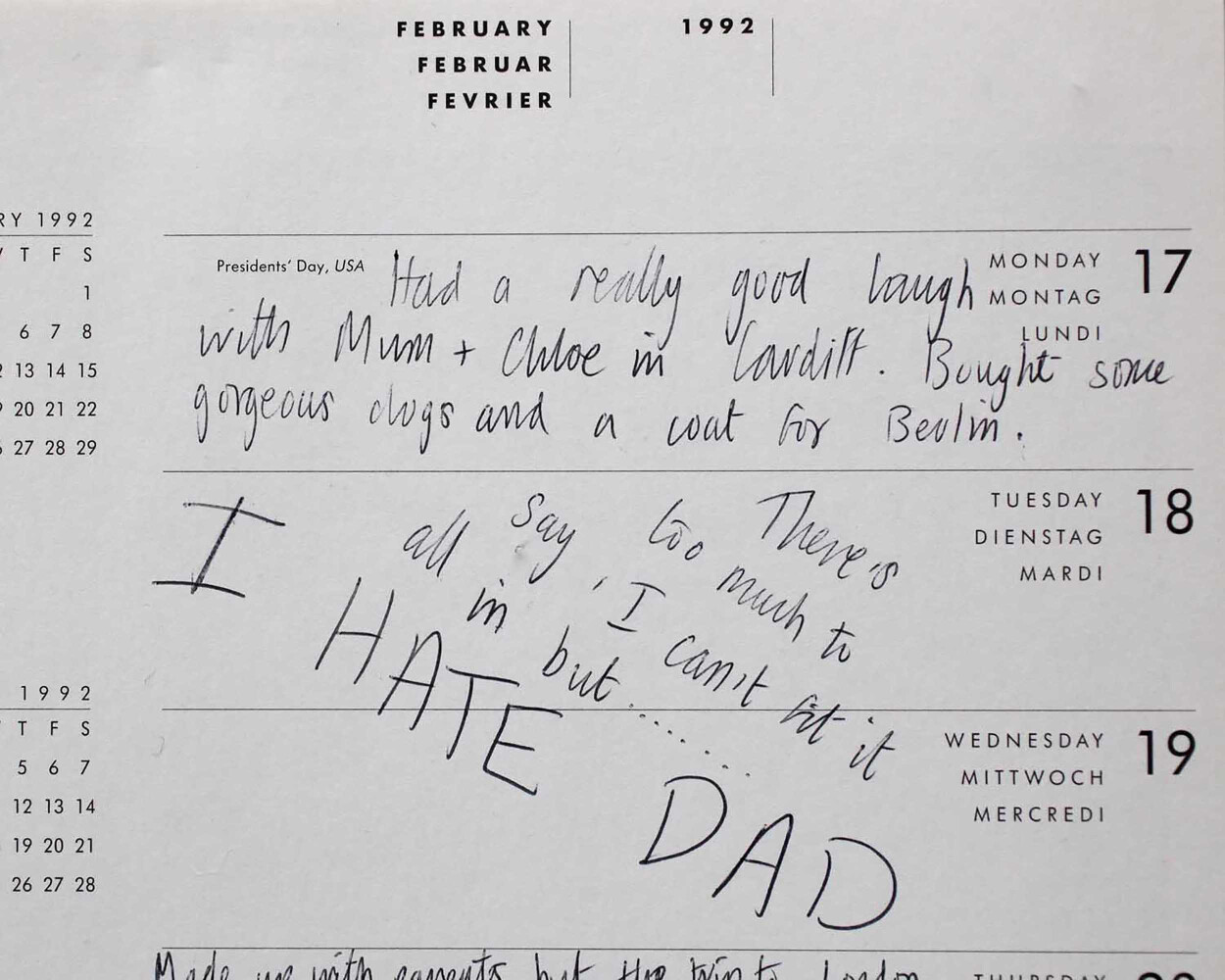

As for me? Well, I don’t remember how I got fat. I do remember being a slightly chubby eight-year-old and being told: “You’ll grow out of it’ it’s just puppy fat.”. But even at that age, I already knew that that word, FAT, was a pejorative term. I felt bad about myself. Not good enough. By the age of 11, I was cycling the two miles to the local shop to spend all my pocket money on Mars bars and eating them secretly before I got home. By 12, I was being taken to Slimming World. The puppy fat hadn’t disappeared – it had set in. By the age of 16, I was almost 16 stone.

-

-

-

-

-

-

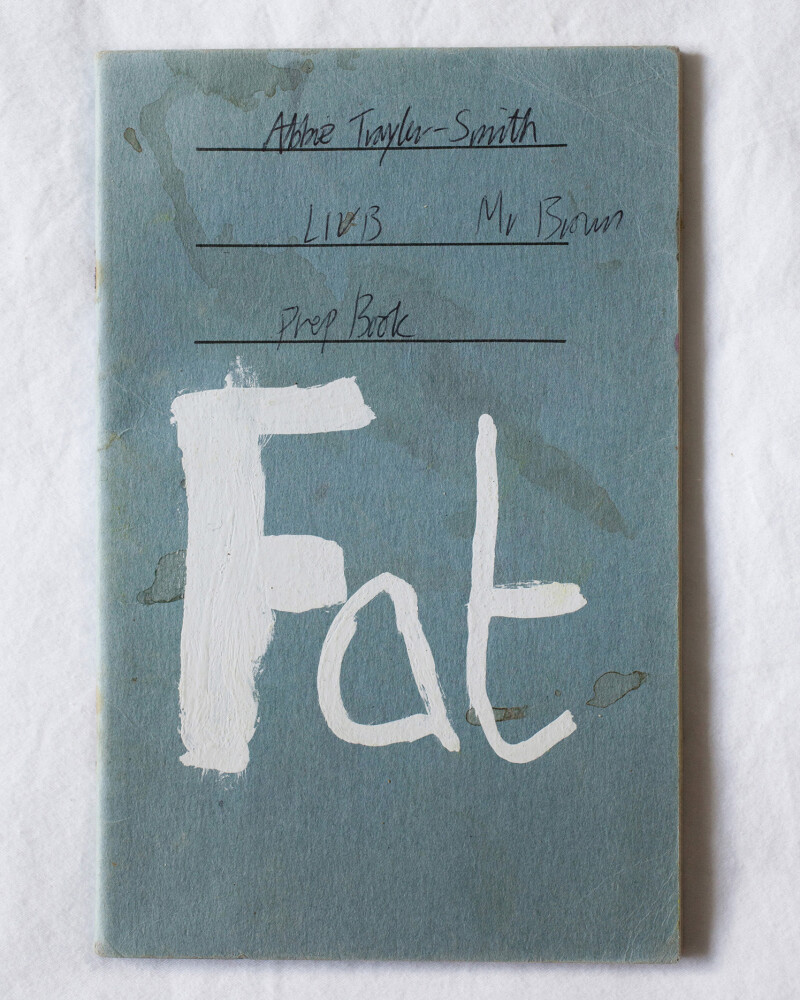

This is an old schoolbook of mine from when I was around 14. Using Tipp-Ex, I wrote FAT on the front of the book to help me stick to my diet. My teenage diaries give me great insight into the way I felt at the time and enable me to connect with my subjects in an emotive and honest way. They have helped me to bridge what can often be an emotional gap between adults and teens about how they’re suffering, especially when it comes to being fat.

It’s too easy to apportion blame. The fact is, we are living in an obesogenic world. Far from being an individual problem, childhood obesity occurs in the context of a social landscape awash with high-calorie, low-nutrition food and sedentary lifestyles. Now there’s evidence that genetics, gut hormones and many other factors play a key role in whether we get fat or not.

The stigma and discrimination surrounding obesity mean the fat get fatter and the problem gets worse. When we individualise the issue of obesity, we moralise it. We point the finger at the person and create shame in the individual, which can have far-reaching consequences.

The shadow of being overweight is something that has followed me throughout my life. One in three kids here in the UK is overweight or obese but we have no idea of how to talk about it. It is engulfed in stigma and taboo, blame and shame.

The aim with this work is to show that this is a complex and nuanced subject that taps into the wider youthful experiences of insecurity and disquiet that so many of us, fat or not, go through with our own bodies and self-image during those formative and insecure teenage years. The experience of being overweight can negatively affect your mental health for years, with the effects of the invisible fat suit never quite leaving you. I want to challenge the stigma and preconceptions around what it means to be ‘fat’ while also questioning the impact obesity is having on society.

Abbie Trayler-Smith

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-